Since the spring, we have been working with Limerick City and County Council on a Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) project on fire safety. The main challenge is to provide fire safety systems to historical buildings using technology. What has been interesting is the number of interwoven issues this has brought up and how widespread the issues are across govtech and smart city projects.

Public Sector Innovation

There has been no shortage of appetite, thankfully, for public innovation in Europe. A recent report from The RSA found that public sector is just as innovative as the private sector. This is no surprise to us. The appetite to achieve more – public good in this case – within constrained resources is a key driver of innovation action and since 2008-2010 the public sector has been left with little choice but to innovate to stretch resource effectiveness.

We have seen amazing innovation projects in the area of govtech, proptech, civic tech and smart cities (including this great looking open call from Govtech Denmark). The projects are usually driven by problem owners and using innovative structures like SBIR enable product co-creation and ideation with a public sector focus. We’re luck to have taken part in two SBIR programmes with local authorities as well as collaborative innovation in the private and non-profit sector with landlords and housing authorities.

These projects generate vast amounts of insight into how technology can be put to use achieving public goals. These projects are satisfying because they often have a version of the “double-bottom line” i.e. we are trying to achieve the dual good of efficiency (or some cost/monetary benefit) and a public good. This is in contrast with private innovation where the latter outcome is a nice-to-have but not essential for success. That public good drives a great deal of additional challenges and it is amazing how frequently we come up against the same sticky issue of administrative capacity when trying to untangle this impact.

Administrative Capacity

A key difference that affects public sector work however is that it often has to consider the vast, overlapping requirements of its related public sector partners. Private sector operators can remain in their silo and deliver innovation. In many cases public sector innovation creates more questions than answers and these questions have to be asked of actors outside of the project.

The projects can also create more data in more verticals. This creates a challenge in management but also in utilisation. Even if we assume the data isn’t personally identifying, there are often multiple uses it can be put to. To give a limited example we can look at core building data to give insight on energy consumption, safety and security. Projects are often led by a department or group with a single focus e.g. environment and energy, so making the data useful for safety and security requires going beyond the project team into the public service and drawing in perspectives and approaches so we can get the most from what has been gathered, measure once and cut twice if you will.

Once we have done that, we then hit the second challenge – management of the data to create the desired solutions. Right now administrations do not have the capacity to manage the kinds of data unlocked by innovation actions. These are often complex and technical datasets, sometimes prescribed in law. Their management needs to be open but also robust and the solutions that are built upon them might have three audiences; the public, administrators and politicians.

Where is the capacity to manage this and to maximise the value of each innovation action come from? Often it becomes part of the project scope and almost always it is a limiting factor on ambitions to provide a better public realm and better public services. It can also be the impetus for shortcuts that lead to projects relying on more personally identifiable information because it seems ‘easier’.

Building Capacity

When we find that certain data can be gathered, how do we turn that to public use? This has happened to us more than once, in our current project with Limerick City, we are actively working on the capacity development because the issue is so important.

So it was interesting to come across two separate pieces this week in which this problem is clearly signposted.

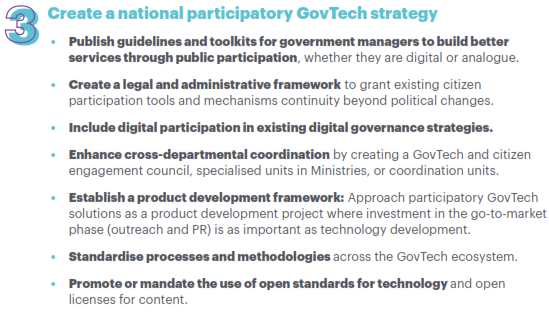

In their fantastic report on Govtech, the Digital Future Society spent half of their conclusions discussing administrative capacity in various guises.

For example, where a smart city commuting project generates data that could potentially identify risks to public health there is an onus to integrate health system perspectives or give them the opportunity to take this work further. There is little capacity for this kind of activity across bodies but a large amount of drive among the professionals to act.

Léan Doody of Arup points to just the same capacity constraints in Smart City projects. An experienced voice in this space and one of our top voices on smart cities her first recommendation for anyone looking into a smart project is:

1. Invest in governance. For cities, ethical digital governance will require investing in new skills and leadership, resourcing a team. As it stands, few cities are fully resourced to manage and control the new data gathered from the citizens they serve. Cities need to define a top-level strategy that includes policies on privacy and the ethical use of data.

Can the smart city be ethical with its data?

The only issue I would take with this is that cities probably need to go beyond strategies, they also need an appendix on execution and resourcing. The government of the future will require a layer that straddles silos and projects and provides an integration service and perspective, helping to maximise value from minimally invasive data. There are many strategies devised and published, not all of them have made it to execution but the lessons now are increasingly clear – a new set of professionals in public service will be needed to enable innovation. The capacity they provide can harness the transformation inherent in smart transport, self-reporting buildings and pervasive environmental mastery into a public-serving good but only with the investment of time and energy.